"Purchase 25 mg promethazine fast delivery, allergy symptoms 7dp5dt".

By: A. Jaffar, M.B. B.CH. B.A.O., Ph.D.

Medical Instructor, Stanford University School of Medicine

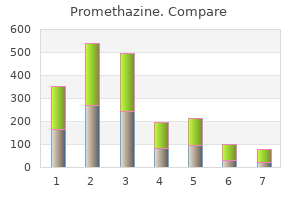

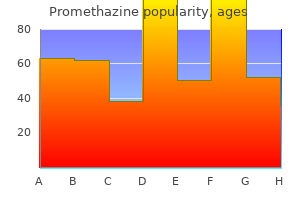

There are two types of piston-tamp llers: dosator machines and dosing-disc machines allergy testing victoria purchase cheap promethazine on-line. In a recent survey of equipment used in production allergy treatment kinesiology proven promethazine 25mg, it was found that dosator machines are used slightly more frequently than dosing disc machines allergy symptoms respiratory buy generic promethazine 25mg on line, with about 18% of the companies responding reporting that they use both types of lling machines [50] allergy and immunology buy promethazine from india. The dosing-disc lling principle has been described [51,52] and is illustrated in. The dosing disc, which forms the base of the dosing or lling chamber, has a number of holes bored through it. A solid brass ``stop' plate slides along the bottom of the dosing-disc to close o these holes, thus forming openings similar to the die cavities of a tablet press. The cavities are indexed under each of the ve sets of pistons so that each plug is compressed ve times per cycle. After the ve tamps, any excess powder is scraped o as the dosing disc indexes to position the plugs over empty capsule bodies where they are ejected by transfer pistons. A capacitance probe senses the powder level and activates an auger feed if the level falls below the preset level. The powder is distributed over the dosing disc by the centrifugal action of the indexing rotation of the disc. Kurihara and Ichikawa [48] reported that variation in ll weight was closely related to the angle of repose of the formulation; however, a minimum point appeared in the plots of the angle of repose vs. Apparently at higher angles of repose, the powders did not have sucient mobility to distribute well under the acceleration of the intermittent indexing motion. At lower angles of repose, the powder was apparently too Їuid to maintain a uniform bed. However, these investigators did not appear to make use of powder compression through tamping, and this complicates the interpretation of their results. Relatively higher values indicate that the interparticulate cohesive and frictional interactions that interfere with powder Їow are relatively more important. Dosing-disc machines generally require that formulations be adequately lubricated for ecient plug ejection, to prevent lming on pistons, and to reduce friction between any sliding components that powder may come in contact with. Some degree of compactibility is important as coherent plugs appear to be desirable for clean, ecient transfer at ejection. However, there may be less of a dependence on formulation compactibility than exists for dosator machines [43]. However, at each station, the powder in the dosing cavities is tamped twice before rotating a Copyright © 2002 Marcel Dekker, Inc. Note the placement of strain gauges on the piston to measure tamping and plug ejection forces (see text). One other dierence is that the powder in the lling chamber is constantly agitated to help in the maintenance of a uniform powder bed depth. Figure 13 illustrates the basic dosator principle, which has been previously described [54,55]. The end of the tube is open and the position of the piston is preset to a particular height to dene a volume (again, Copyright © 2002 Marcel Dekker, Inc. In operation, the dosator is plunged down into a powder bed maintained at a constant preset level by agitators and scrapers. Powder enters the open end and is slightly compressed against the piston (sometimes termed ``precompression' [54]). The dosator, bearing the plug, is withdrawn from the powder hopper and is moved over to the empty capsule body where the piston is pushed downward to eject the plug. In certain machines, such as the Macofar machines, the body bushing is rotated into position under the dosator to receive the ejected plug [56]. A secondary control of weight is the height of the powder bed into which the dosator dips. In one of the earliest reports evaluating the Zanasi machine, Stoyle [55] suggested that formulations should have the following characteristics for successful lling: 1. Fluidity is important for powder feed from the reservoir to the dipping bed and also to permit ecient closing in of the hole left by the dosator. A degree of compactibility is important to prevent loss of material from the end of the plug during transport to the capsule shell. It was suggested that low bulk density materials or those that contain entrapped air may not consolidate well and that capping similar to that which occurs in tableting may result.

Habitual circulation there certainly is allergy shots user reviews order promethazine in india, but no sense of long-term or even necessarily short-term equilibrium allergy treatment in quran promethazine 25 mg visa. Rather "Stoffwechsel" expresses a sense of creativity in much the same way that Benjamin talks about mimesis: the metabolism of nature is always already a production of nature in which neither society nor nature can be stabilized with the fixity implied by their ideological separation allergy testing vernon bc buy 25 mg promethazine with amex. The ideology of separate and distinct social and natural spheres therefore begs the question: for what purpose? There are many layers to an answer allergy shots for pet dander cheap 25mg promethazine mastercard, but most simply, the positing of an external nature rationalizes and justifies the unprecedented exploitation of nature (human cum non-human), the "massive racket" that capitalism, historically and geographically, represents. Political ecology provides a powerful means of cracking the abstractions of this discussion about the metabolism or production of nature. Rooted in social and political theory it is also grounded in ecology and has an international scope. When complemented by an environmental justice politics, which is less internationally focused and less theoretical but more politically activist in inspiration, political ecology becomes a potent weapon for comprehending produced natures. While all of these ideas have come together powerfully in the last two decades or more, they are only now being applied explicitly to urban nature. If they are going to have theoretical and political traction, however, these ideas need to be tested in the most produced nature of all, and that means the city. The production of urban nature is deeply political but it has also received far less scrutiny and seems far less visible, precisely because the arrangement of asphalt and concrete, water mains and garbage dumps, cars and subways seems so inimical to our intuitive sense of (external) nature. Whatever our analytical sophistication, the idea of nature as a contrivance still cuts deeply and sharply against our most engrained and peculiar prejudices. In the Nature of Cities helps open up this new territory and it will help to create a new structure of feeling connecting nature and the city. Radically new ideas are by definition discomfiting: only later do they seem "natural". It is a search for ways to articulate a creative politics of nature in, of and for the city. The emphasis on urban metabolism represents a sober recognition of the power of capitalist productions of nature while winkling them open at points of opportunity for radical, even revolutionary, change. It broadly rejects the apocalyptic "death" of nature in recognition of the fact that, however perversely, societies make the natural environment they live in, to a lesser or greater degree, although not of course under conditions of their own choosing. Nature is manifestly not dead but is incessantly reproduced-in ways we may detest or we may love. Nor is environmentalism dead, despite the belated recognition by some among the mainstream environmental movement that they have motored themselves to the end wall of their own political cul-de-sac. As part of a broader political movement, an urban political ecology can help integrate a politics of nature into a more established "social" politics; at the same time an ecologically enhanced politics focusing on the productive metabolism of nature can further exoticize the absurd separation of nature and society while denying any anti-social universalism of nature. In the bigger picture, seeing the world so differently-outside the prism of capitalist nature-requires both analytical and poetic exploration. But insofar as the landscapes we create refract back to us a very powerful naturalization of the social assumptions that sculpted such landscapes in the first place, a revolution in our thinking may be intimately bound up with a revolution in how these landscapes are made. Seeing the world differently probably depends on making a different world from which the world itself can be seen differently. At the same time, the "urbanization of consciousness" constitutes Nature as well as Space. Global capital moved spasmodically from place to place, leaving cities like Jakarta with a social and physical wasteland where dozens of unfinished skyscrapers were dotted over the landscape while thousands of unemployed children, women, and men were roaming the streets in search of survival. Puddles of stagnant water in the defunct concrete buildings that had once promised continuing capital accumulation for Indonesia became great ecological niches for a rapid explosion of mosquitoes. This example is just one among many to suggest how cities are dense networks of interwoven socio-spatial processes that are simultaneously local and global, human and physical, cultural and organic. The myriad transformations and metabolisms that support In the nature of cities 2 and maintain urban life, such as, for example, water, food, computers or hamburgers always combine infinitely connected physical and social processes (Latour 1993; Latour and Hermant 1998; Swyngedouw 1999). The world is rapidly approaching a situation in which most people live in cities, often mega-cities. It is surprising, therefore, that in the burgeoning literature on environmental sustainability and environmental politics, the urban environment is often neglected or forgotten as attention is focused on "global" problems like climate change, deforestation, desertification, and the like.

Buy promethazine 25 mg mastercard. Myghad this allergies.mp4.

For example allergy testing utah purchase promethazine 25mg line, a rich vein of research on nature reserves and biodiversity conservation has exposed the continuity of "fortress-style" conservation with colonial practices of indigenous dispossession allergy testing mayo clinic discount 25 mg promethazine fast delivery. In place of often oppressive systems of natural resource management by (and often for) scientific elites allergy tracker promethazine 25 mg generic, political ecologists have promoted community-based resource management as a more just alternative (Brosius et al allergy shots charlotte nc purchase promethazine 25mg with amex. Participation gives local people a voice, and so is consistent with procedural ideas of environmental justice as recognition. It is also more attuned to local livelihoods and so is arguably also better placed to secure the just outcomes emphasized by consequentialist theories of environmental justice (Shrader-Frechette 2002). Second, in response to these normative demands for public participation, many government agencies are themselves now trying to incorporate more participation by the public in their science and science-based policy making, albeit often for instrumental as much as normative reasons. As Alan Irwin (2006: 306) has observed, the participatory turn in science-based policy making has sometimes failed to acknowledge how public dialogue can "create further grounds for criticism and concern" rather than political consensus. While there is now a growing literature in science studies evaluating public engagement schemes and offering best practice recommendations. Chilvers 2009), political ecologists have tended to follow Foucault in critiquing these instrumental visions of participation as disciplinary mechanisms for molding individuals into self-regulating "environmental subjects. Third, normative and instrumental rationales for public participation often find common ground in the seductive promise that it will also increase the quality of science and sciencebased policy. Likewise, many political ecologists insist that community participation in natural resource management will also lead to more effective and ecologically sensitive forms of environmental conservation than coercive systems of technocratic management by scientific experts (Adams 2001; Brosius et al. Such claims about the substantive contributions of public participation to science and science-based policy are beset by some fundamental ambiguities. To explore them further, I want to return for a moment to Ulrich Beck, both because his theory of reflexive modernization is influential in its own right and because it starkly illustrates the ambiguity about the wider claims made in science studies and political ecology about the value and purpose of public participation in science and science-based policy. Beck (1992a: 119) writes: the public sphere, in co-operation with a kind of "public science" would be charged as a second centre of "discursive checking" of scientific laboratory results. What kind of "discursive checking" does Beck hope the public will perform in his "upper house"? Here the role for the public upper house would be to apply the normative "standard `How do we wish to live? In this role, the public or political sphere is responsible for regulating the techno-scientific innovation undertaken in the lower house of science. This vision depends on already established distinctions between the scientific work of discovery and the political work of agreeing on the values to regulate its development and application. As such Beck may sound more like a description of the status quo than some new, more reflexive modernization, but this apparent contradiction might be resolved if it were read as a call for "upstream" public engagement in science itself (Figure 17. It called for engagement with the public to be moved "upstream" into the heart of the scientific research process where research agendas can be shaped and steered in publicly acceptable ways, rather than, as has been more typical of "downstream" public consultations, waiting until after the invention of new technologies before worrying about how to regulate them. For political ecologists, the idea of upstream public engagement might help to formalize and thereby strengthen the role for the public in their otherwise often rather vaguely articulated appeals to participatory action research as a research methodology. Rather than dissolving entirely the distinctions between science and politics, this vision of participation as normative steering would make the institutional boundaries between them more porous while at the same time preserving the epistemic distinction between facts and values. The role for the public would be assessing "the values, visions and assumptions that usually lie hidden [i]n the theatre of science and technology" (Wilsdon and Willis 2004: 24). Public participation here serves a normative role, steering the direction science goes and deciding what goods science should serve, not the epistemic one of judging sound science or evaluating the truth of its epistemic claims. Two problems, at once of principle and of practice, plague the ideal of participation as normative steering. How should participants be chosen to (a) Open upper chamber for the lay public Discursive checking of scienti c risks and applications Settled facts and "what if" risk assessments (b) Open upper chamber for the lay public "Upstream public engagement" in science Lower house of science Lower house of science Figure 17. Demeritt ensure that their normative judgments reflect those of the wider public they serve and represent? One persistent complaint about public engagement exercises is that they fail to represent the views of the "silent majority" (Irwin 2006). Similarly political ecologists have noted that participation in community resource management schemes is often skewed towards local elites and can reinforce existing inequalities based on caste, class, and gender (Agrawal 2005). But that same critique might also be turned inwards on political ecology itself, whose paternalistic tradition of radical vanguardism has not always encouraged reflexivity about the effects of its own interventions. How can the public license the decisions taken by participants acting in its name but, unlike elected officials, not directly accountable to it through the ballot box? In practice, however, the institutional imperative for participatory exercises is often precisely to create enough distance between elected officials and controversial regulatory decisions to allow for blame avoidance and political deniability. Indeed, as Rothstein (2007) notes, it is precisely among such unelected and weakly accountable arms of the regulatory state where the enthusiasm for public engagement has been greatest.

At the same time allergy symptoms only at night discount promethazine 25mg without a prescription, social injustice was situated firmly within broader structural conditions allergy vs sensitivity vs intolerance purchase promethazine 25mg with mastercard, such as those created by the world market system allergy medicine effects order promethazine 25mg visa, from dependency to inequality (Wallerstein 1974; Frank 1969; 575 W allergy relief vitamins buy promethazine 25 mg mastercard. The rise of subaltern studies in the 1980s also figured prominently in a new theoretical framing of resistance and social movements (Guha 1997; Spivak 1988a). As a project to rethink history (especially national histories) from the perspective of the subaltern, subaltern studies was a reaction to both Marxist and liberal interpretations of history as linear and neat, written from the perspective of elites. Subaltern studies scholars insisted that multiple histories lay hidden in the silences and cracks of official narratives, and that a proactive agenda was required to ferret out the meanings of (and from) the margins (Spivak 1988b, 1993, 2004). All of these concerns influenced the study of social mobilization within political ecology, a field that itself came into being in tandem with the proliferation of new social movements around the world. Unlike many other fields of study, political ecology retains its focus on the struggles of agrarian and marginalized populations, highlighting the complex ways in which power relations condition mobilization and resistance, and with what effects. We explore these specific contributions in the overview that follows, beginning with the centrality of meaning norms, values, customs and ideologies in ecological conflicts and contestations. Like Thompson, Scott argued that rebellion was directly linked to normative conceptions of obligation, right and reciprocity. Judith Carney and Michael Watts (1990, see also Carney 2004) built on this perspective to illustrate how pre-colonial moral economies guiding access to land shaped the repeated "failure" of intensive rice production schemes in the Gambia. Women, in particular, resisted attempts to intensify production on land to which they would no longer have a claim, given its incorporation into "community resources. As he argues, "It is only through a full and critical engagement with both the materiality which underlies all social life 576 Social movements and the moral claims that implicate natural resource use that the etiology of resource-related conflict can be better understood. Struggles over resources are often only superficially so-they in fact reflect not only broader tensions (with ethical dimensions) between social groups but also tensions within these groups" (866). Bebbington has worked with communities, non-governmental organizations and social movements and argues that there are many different ways "to be an Indian" in the highlands of Ecuador (1991, 1993, 2004) and, as such, research should focus not on romanticized notions of tradition but should analyze and situate the moral economies of modernization (Valdivia 2005). In short, these competing moral economies were born out of the inherently relational practice of struggle in a moment of capitalist entrenchment. American West who fought against state control of public land and mobilized for the right to commodity production on federally-owned lands from the late-1980s to mid-1990s. McCarthy illustrated the ways in which Wise Use activists and campaigns drew upon similar sorts of populist claims as the movements studied in the global south, with appeals to self-determination, local knowledge and local rights. While this moral economy was not framed as anti-capitalist, it did constitute an "ongoing struggle over nature" and "resistance to the perennial dynamics of capitalism" through their articulation of an alternative set of economic relations that maintained the conditions, livelihoods and culture of rural Western communities (2002: 1291). Though diverse in their geographic, historical and cultural locations, these studies illustrate the centrality of meaning in contestations over resources and environments in the context of capitalist change. These meanings of course are not created in a vacuum; they are constituted in and by particular people, places and times. Grounding mobilization: the importance of place In part because of its close connection to the disciplines of geography and anthropology and in part because of its focus on land managers and material practice, political ecology has always emphasized the importance of place in shaping the conditions of exploitation and of protest or mobilization; if nature and society are co-constituted then by definition location matters. Political ecologists such as Christian Kull working on social mobilization situate movements and protest in historically rich descriptions of local environments and ecologies (2004). Keene He argues that the peoples of the Pacific coast region have been shaped by an articulation of processes that have simultaneously produced the region, including historical processes of geological and biological formation, the daily practices of local black, indigenous and mestizo groups, capital accumulation, incorporation into the state, and cultural political practices of social movements (2008: 31). This focus on the importance of place is visible in studies of indigenous peoples and indigeneity more generally. In Cocahabamba, Bolivia, where the water wars erupted in 2003, most observers focused on urban movements in organizing the protests but Perreault argues that peasant movements were actually far more important and organized in utilizing the power of traditional discourses around usos y costumbres (customs and habits) to manage water and shape new forms of governance. With Gabriela Valdivia, Perreault has also done important work on the role of place in shaping mobilization around new resource imaginaries (2010; see also Wolford 2005). Valdivia and Perreault compare mobilizations against the privatization of natural gas in Bolivia and oil in Ecuador to demonstrate the importance of historically situated, place-based notions of citizenship and nation. Moore argues that colonial and post-colonial forms of governance called upon fixed lines and spatial concentrations government spaces and settlement areas that violated the fluid spaces of house and field in traditional societies and in the newly created squatter areas. These studies help us to ground movements and mobilization in particular historical and geographic locations, without neglecting the broader global processes within which they are constituted. How do these inform social struggles and the environments in and for which they are waged? While movement discourses are inextricably connected to the cultural values and norms that give them meaning, they do additional work of shaping the contours of resistance defining what (and who) is to be included and excluded, and the terms of their inclusion. Narratives and discourses are deeply political, as demonstrated below, and can have unintended effects as they travel back and forth through time and space.